Our Lilly, the Boston terrier, quivered on the drive to the oncology surgeon’s office. Cuddles with her blanket and favorite toy, Hedgie, offered little comfort. So, too, the .05mg of clonidine coursing through her system.

The day had come to remove the plumb-sized tumor, a locally-aggressive sarcoma, from her right foreleg joint. We moved the surgery date up two weeks because the tumor swelled since our consult appointment. The surgeon expressed concern that waiting could complicate the excision.

I reached over the console to pet Lilly in the front seat. She calmed for a second, then shuddered soon as I removed my hand. I replaced it on the scruff of her neck. Again, she settled. Not until we pulled into the clinic’s driveway had I noticed the shallowness of my own breaths.

During that previous visit, Doctor S. told my wife and me about the two ways to achieve clean margins. First, a radical procedure: grafting muscle from her right shoulder onto muscles supporting the elbow. This option carried high risks for necrosis and dehiscence (graft failure and detachment). Second, total limb amputation. No residual disease. No more chasing her furry chicken.

We chose a less invasive option. Remove the gross tumor leaving microscopic disease and a fair chance of recurrence, depending on the tumor grade. A chest x-ray and abdominal scan showed no evidence of metastasis, bolstering our confidence that Lilly’s tumor was low-grade.

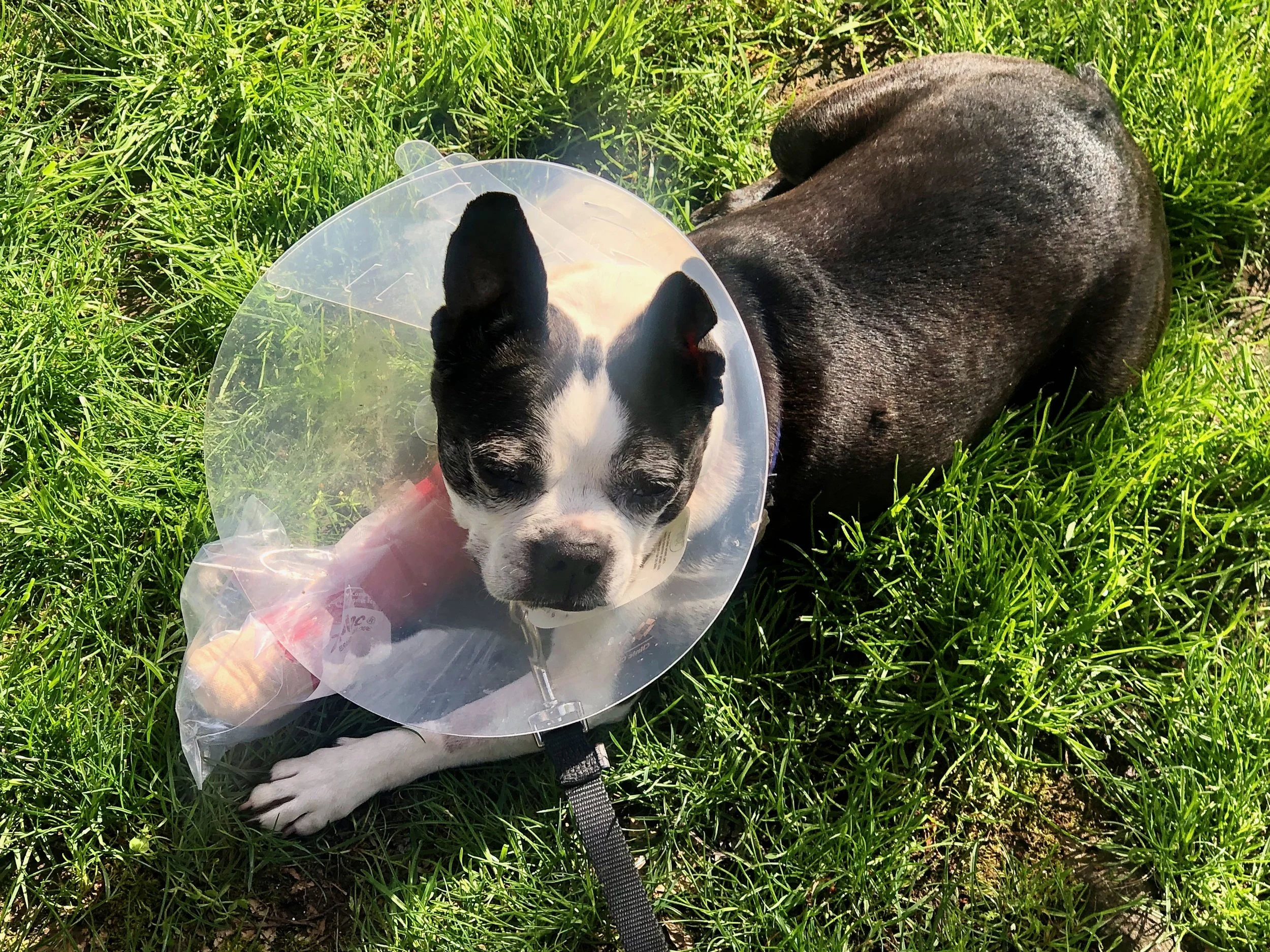

I walked into the clinic on surgery day, Lilly cradled in my arms. She turned her head away from me as I kissed her crown and passed her to the vet tech; her predictable posture whenever she’s left where she’d rather not be. I picked Lilly up after surgery, her eyes brimming with forgiveness. Or, perhaps bleary from meds. Minimal activity for two weeks. No running or jumping. Gabapentin for pain, Trazodone to mellow the brain. Biopsy sent to lab for grading.

Lilly’s incision healed well. Elizabethan collar and stitches removed, Lilly waited with me in the exam room for Doctor S. and her follow-up report. She, chomping playfully on Hedgie’s nose. Me, emitting my (hopefully) last gasp of angst. Statistically, there was an 85 percent chance that Lilly’s tumor was either grade 1 or 2.

Doctor S. walked in the exam room. I knew it before she spoke the words. Saw them behind the tilt of her head and her flatlined lips right after she said how clean her surgery site looked. Here it comes, I thought. The shit side of the Oreo cookie. I shrunk into the corner of the exam room, a boxer on the ropes, gloves guarding my face from a one-two punch: Grade 3. Seventy-five percent chance of recurrence and metastasis. Doctor S. gazed at me with warmth and compassion, the only way one can deliver such blows by the dozens in their daily work.

Then, she threw us a lifeline: electro-chemotherapy. The relatively new therapy modality involves administering chemotherapy while pulsing electricity near the tumor site with a special probe. Electro-chemotherapy might zap some residual tumor cells while holding others at bay. Minimal side effects: possible mild swelling and ulceration. Nothing compared to the fatigue and whirling guts of traditional chemo and radiation. Our consult appointment is scheduled for tomorrow.

My wife and I are still digesting the news about Lilly’s projected shelf-life. A big question mark. Possibly, 12 months with intervention. Beyond that, gravy. She’ll likely see her 13th birthday in October.

That celebration begins now.