Loving a rescue can teach one to forgive the humans in one’s life - including oneself.

Two weeks ago, I was sitting with my dad and mama Gloria (“step-mother” is not in my vocabulary) and the Compensation and Pension Officer who was interviewing my dad about his combat experience during World War II.

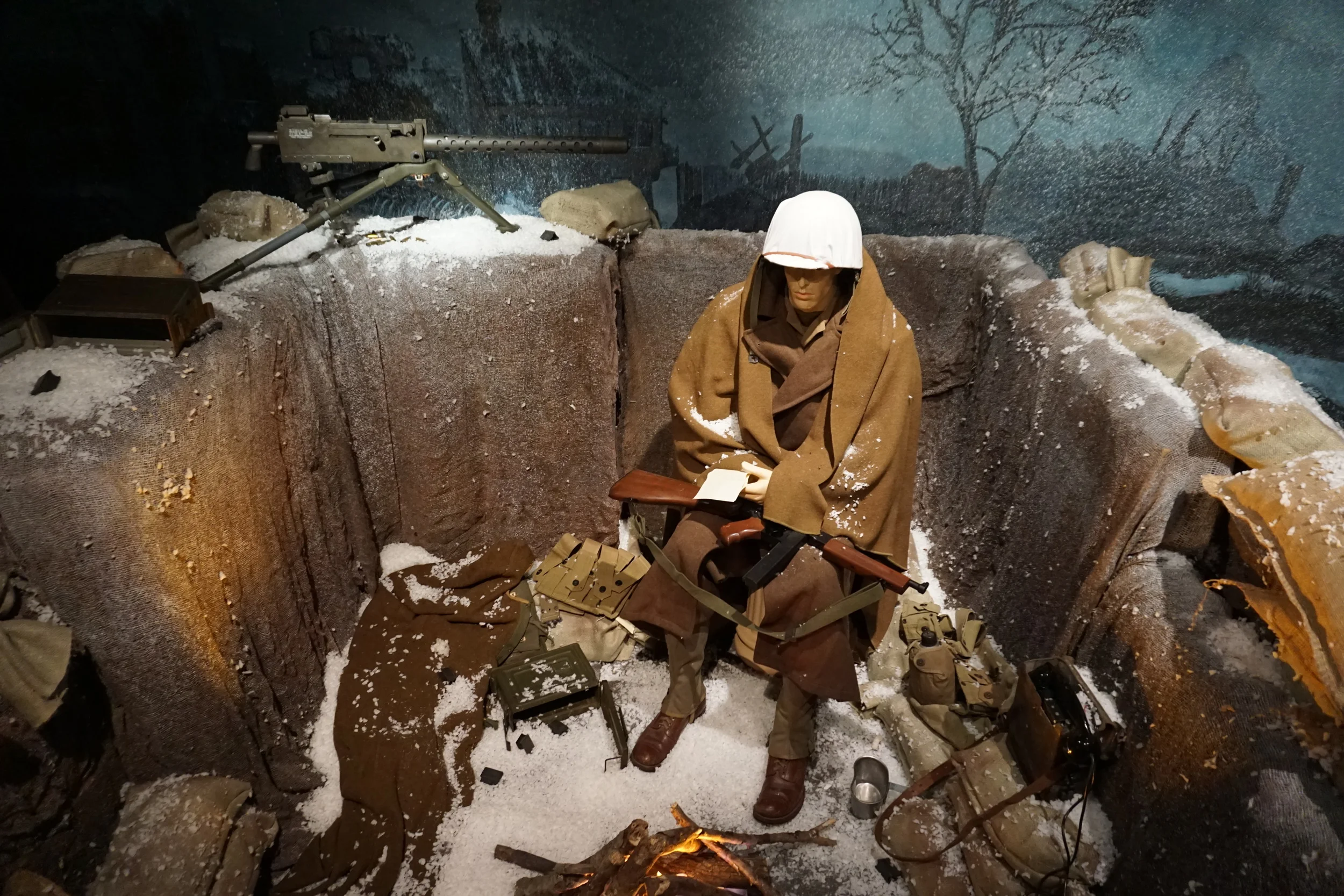

As my dad told of how he saw his commanding officer eviscerated by an exploding 88mm mortar a few feet away from him in that fox hole at the Battle of the Bulge, I felt an explosion in my own head and heart.

Suddenly, it all made sense. Dad’s drinking. His bombastic temper. The dismissing of people - including me - who disappointed him. What had remained locked in the attic of dad’s psyche for 70 years came pouring out with the ferocity of a thousand revelations. My dad’s every word unleashed a torrent of empathy from places within me I never knew existed.

For decades I felt oh so superior to my dad in my abilities to comfort and nurture. Then, I became father to Louie, a troubled Boston-terrier-Boxer mix who developed inexplicable fear-biting behaviors several months after we had adopted him. Our love, training and behavioral interventions were not enough to turn Louie around. With aching hearts, my wife and me surrendered Louie back to the agency from where we adopted him.

Louie ultimately found a new home on a ranch in Orange County, but my home would not be the same again. I cried for months over the loss of Louie and seethed with resentment toward myself as an inadequate pet parent.

I thought I’d processed these feelings sufficiently through therapy and journaling to enable my wife and me to adopt once again. Lilly, the Boston terrier, has been nothing short of a joy, though she arrived with her own set of challenges. Louie mistrusted tall, bent-over men. Lilly flew into hysterics upon meeting new dogs. With both Louie and Lilly, my temper has been challenged. Honestly, I have not always reacted like the paragon of patience I imagined myself to be.

During my moments of exasperation toward my fur-kids, I hadn’t thought for a second that I was acting toward them as my dad had toward me when I performed at less than my best. Then, I was privileged enough to have a window into my dad’s life that, until that interview, he’d kept firmly shuddered.

Looking through that window, I saw two men, each harboring their own agenda of self-loathing for what more they could have done so that others may have lived - or lived better than they had. Both my dad and me have done - and are doing - the best we can given who we were and what we had then, and who we are and what we have now.

Were it not for Louie and Lilly, my own attic window may have never been opened.

For the “son” that is gone and the “daughter” that remains, I owe the deepest gratitude this holiday season - and every day of my life.